Workshop

Research Proposal

Kennedy O’Hanley

May 13th

9110 Stephens Manor Dr.

Mechanicsville VA, 23116

5/13/2020

Dear National Institute of Child Health and Human Development,

The purpose of this research is to determine if infant mortality in Ethiopia could be decreased, if women had to travel less to get to the nearest healthcare facility for post-natal care. I would like to apply for funds to complete my research. Ethiopia does not have an adequate health care system. The infant mortality rate is about 39.1 deaths per 1,000 live births. Some women have to travel hours to reach hospitals and healthcare facilities, and because of this distance, are usually unable to make that trip several times after the birth of a child to attend postnatal care. This leads to many infants and children under five dying of preventable infections and diseases. In Ethiopia, 80% of newborn deaths are caused by treatable cases. The infants in Ethiopia are dying not only because of the travel time to adequate healthcare facilities, but also because there is an economic gap dividing the groups of women, and determining that some have the right to necessary resources, and others do not simply because they do not have the money. By funneling in money, resources, and new healthcare facilities and hospitals, infant mortality would decrease because women wouldn’t have to travel so far to safely give birth. Ethiopian women should not have to go through the pain of losing a child simply because their country does not have the resources to take care of it’s people. Too many infants are dying in Ethiopia, and also all around the world. There is a specific data model that could help alleviate the number of infant mortalities in Ethiopia: a Bayesian Hierarchical model. This has not yet been done in Ethiopia, but could be incredibly helpful in determining where best to funnel resources and capital. Since the resources in Ethiopia are limited and the resources they do have are inadequate, the neonatal and maternal mortality is much higher than it should be. Human lives are at risk each and every moment in Ethiopia. I believe this research could do extraordinarily well in improving the lives of women and their newborns. With the capital to make this research happen, we could catapulte Ethiopia’s extremely high infant mortality rate to something much more reasonable, and we could save the lives of an unimaginable amount of infants.

Thank you for your time and consideration,

Kennedy O’Hanley

Problem Statement

Every year, around 303,000 women die due to complications from childbirth. That is 303,000 families who mourn the death of a sister, daughter, aunt, and mother. This is a shockingly high statistic, yet what is even more staggering is the infant mortality rate. Around 4.1 million infants die in childbirth every year. The countries with the highest infant mortality rate are as follows: Afghanistan with 110 deaths per every one thousand births, Somalia with 94 deaths per every one thousand live births, and Central African Republic with 84 deaths per every one thousand births. This is extremely and devastatingly high. For my research specifically, I am going to be looking at Ethiopia and delving into how it is handling its high infant mortality rate: about 49 deaths per every one thousand live births. Along with this, around 15,000 children under the age of five die every day around the world. These children die due to numerous conditions, diseases, and situations. Specifically in third world countries, however, these children are mainly dying due to a lack in resources and facilities. These infant mortality rates and children under five mortality rates are housing too many preventable cases. By a shortage of the correct and adequate resources, these overwhelming death statistics could lower. All it takes is an efficient allocation of capital, and the lives of so many mothers, children, and families drastically improves.

Every woman deserves the resources and healthcare facilities necessary for performing a safe birth, both for the mother and child’s benefit. This takes on Amartya Sen’s “friendly” approach to human development. There are unfreedoms done to entire groups of people, when there is an economic gap that divides those that are able to give birth safely and comfortably, verus those who must walk hours or even days just to get to an underfunded, overcrowded healthcare facility that isn’t even neonatal focused. One of Amartya Sen’s main philosophical beliefs was that poverty and poorness block individual freedoms. This is evident both in Ethiopia and in third world countries all over the map. In the United States, the per capita income is $63,690, whereas in Ethiopia, the per capita income is $790. The economic gap divides groups of women, and essentially says that some women don’t deserve the safety for them and their children in the same way that the women above the economic gap do. To put things in perspective, the state of Virginia has a population of around 8.5 million, and Virginia has around 1,243 healthcare facilities. Ethiopia has a population of around 105.4 million, and they have only 228 health care facilities. More than 500,000 women and girls from Ethiopia suffer from disabilities caused by complications caused by childbirth each year. In Ethiopia, 80% of newborn deaths are caused by treatable cases. The neonatal mortality rate accounts for 41% of under-five-years old deaths. Compared to the United States, a mother is twenty five times more likely to die during childbirth, and an infant is nine times more likely to die before reaching the age of one. This is unjust, and this issue needs more people utilizing the newest data science platforms and technologies, in order to figure out how to bridge the gap. This problem could be hugely benefited by an increase of healthcare facilities and resources going to those women who need it most.

The harms I am seeking to address are using new data science to better equip women in under-developed countries for childbirth and pregnancy. There are many women losing their lives and their babies in these areas due to insufficient resources and a lack of funding and facilities. Specifically in Ethiopia, 80% of newborn deaths are caused by treatable cases. The neonatal mortality rate accounts for 41% of under-five-years old deaths. These statistics are staggeringly high. Along with infants, mothers are also at risk. Women have a one in fifty-two chance of dying from childbirth each year. The lives of so many people are risked simply by getting pregnant and giving birth. This is happening because Ethiopia, and many other third world countries don’t have the resources or facilities to properly care for women during this stage of life. There is about one midwife per 1,500 births, making it impossible for each woman to get the care and treatment she and her baby need. There is also a need for improvements in vaccination for children under five in other parts of the world as well. Many children aren’t getting the care or medicine they need. These problems could hugely benefit by having more access to resources and healthcare and emergency facilities.

There are several reasons that Ethiopia has yet to implement a system that would decrease child mortality and increase attendance in postnatal care, and better resources and conditions for mothers. In all of Ethiopia, there are few healthcare centers. Some women have to travel through very tough terrain to get to these healthcare facilities. The terrain in Ethiopia is extremely mountainous, and the Ethiopian landscape is mainly formed from a high volcanic plateau. Along with this, the majority of Ethiopia has a very hot climate, due to its closeness to the equator. As one can imagine, the climate coupled with traveling four hours to reach a healthcare facility, which is understaffed and underfunded, is not exactly ideal for women in labor or those who are close to childbirth. Because of this, many women opt to give birth at home with a midwife, or decide to make the long trek to a hospital, but will not go back for postnatal health care. This decision is understandable considering many healthcare facilities do not even have properly trained professionals to aid women in the birthing process. However, not attending postnatal care has a strong correlation with a high infant mortality rate. With the use of several different technologies, the areas in Ethiopia that require more resources can be determined, and we can figure out which places most need new healthcare providers and more resources. In order to pinpoint exactly where we could allocate resources, we need to use data science methods that can take in multiple parameters. By using multiple covariates, we will be able to form a more accurate map of where women of child-bearing age reside, and how we can aid them, so that they aren’t walking across the country to get what they need and deserve. Personally, I don’t believe this problem is a complex adaptive system. I believe that we have the tools and data out there to determine and understand what Ethiopia, and countries like Ethiopia need. It is more a problem of resources. Recently, Ethiopia has a more stable political and economic situation. If they could figure out, with the help of other stable countries, how to allocate resources and loans effectively, then more money and funding could be put into healthcare resources in Ethiopia. There are many problems with the current quantity and quality of their healthcare facilities, and women are arguably the most impacted. Using bayesian models and geospatial data, we can figure out exactly where it would be most efficient to build more hospitals and funnel in resources.

The main focus of the research in neonatal and maternal health and safety improvement focuses on pinpointing where women of child-bearing age reside, and how close they are, or how easy it is for these women to get the help they need. When a woman is pregnant, she will need easy access to several things; vitamins and supplements, a certified healthcare worker, and facilities that are equipped enough to take care of women who are giving birth. These women need to be able to get to facilities and have access to health care workers in an adequate amount of time, and right now there are not nearly enough hospitals or workers to supply these women with necessary resources. In order to help improve upon the lives of these women, we need to figure out where the population resides, and which areas would be most efficient to place more healthcare facilities, and which areas need more resources than others. We can use data science to pinpoint directly these areas in which funding and contributing to the process of building and providing extra healthcare facilities for Ethiopia would be best spent.

The time it takes to travel to healthcare facilities does have an effect on infant mortality, and for that matter, a great impact. By funneling in money, resources, and new healthcare facilities and hospitals, infant mortality would decrease because women wouldn’t have to travel so far to safely give birth. Ethiopian women should not have to go through the pain of losing a child simply because their country does not have the resources to take care of it’s people. In fact, no woman should have to experience that pain, and it is horrible to think of the many families in this position everyday, simply because the country they live in is more poor than the rest of the world. Too many infants are dying in Ethiopia, and also all around the world. The statistics and percentages of the deaths of these babies and infants are appalling. This could be alleviated if we allocate the correct amount of resources to areas that need it. In order to truly lessen the infant mortality rate in Ethiopia, travel time for women must be decreased.

Literature Review

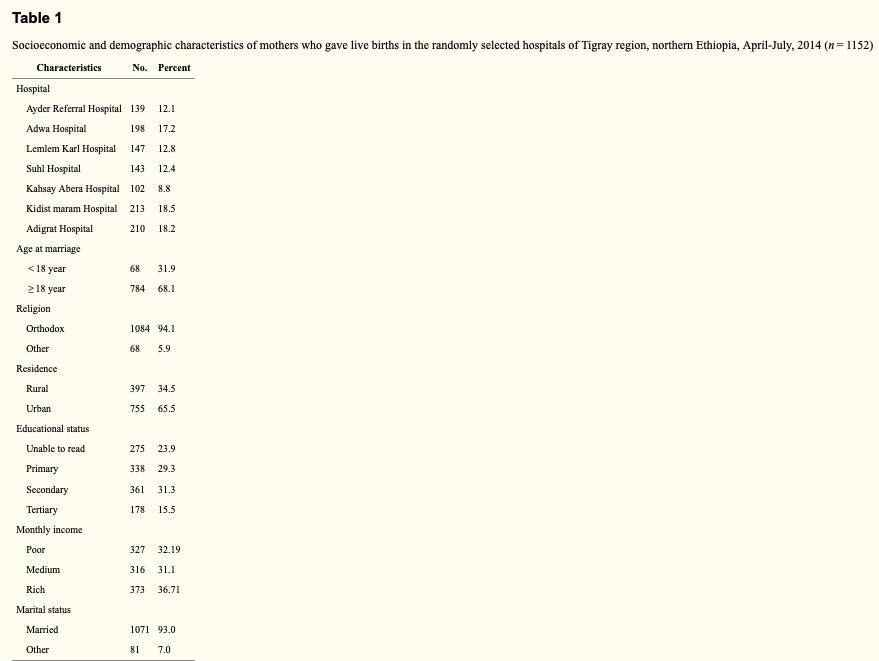

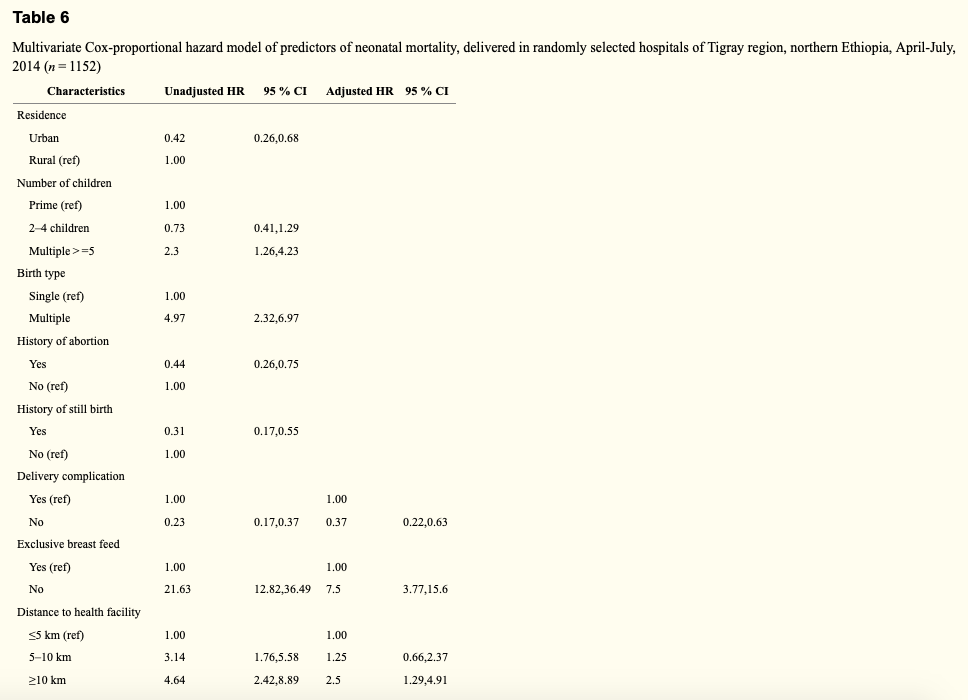

The data in Survival of neonates and predictors of their mortality in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia: prospective cohort study, is used to determine which covariates trump all others. There are several models and techniques used, and with several variables, and the authors work to investigate which covariate has a higher influence over infant mortality. Distance to the nearest health care facility was among the most dominant independent variables. Along with this, there was data that showed a higher infant mortality rate from those women residing in remote or hard to reach locations, indicating an inadequate amount of resources to all women. The data for this study was processed through STATA version 11.1. The authors used Kaplan-Meier curves to estimate the survival times of the infants. The ultimate goal of the study was to determine the true factors in why the infant mortality rate is so high in Ethiopia, so a Cox-proportional hazard regression model was used to identify these factors. The authors collected their data using a survey. They first created a questionnaire, and then had two trained midwives interview mothers within six hours of giving birth. Mothers and infants were tracked for twenty-eight days: each day they were in the hospital, and then every seven days after that. This ensured that data could be collected at every step of the way. This study had both a spatial and temporal dimension. The authors collected data based on travel time to facilities, where mothers were residing and what conditions they were living in, and the time of death of those infants who did die. There were no variables or covariates that impacted the Cox-proportional hazard regression model negatively or incorrectly.

This model is a very accurate depiction of how Ethiopia’s healthcare system is failing the women of the country greatly. In Survival of neonates and predictors of their mortality in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia: prospective cohort study, the authors use a Cox-proportional hazard regression to look at survival rates of infants due to travel times. This model is built to analyze travel times, and determine the most influential covariates. The hazard rate models what the effect of the specific variable is. The authors used this data to input many variables and compare them to which infants died. There were many different variables, including travel time to healthcare facilities, home situations, economic need, and more. This model gives a way to determine how long a child will survive for in each condition. It is a useful survival method that helps to accurately narrow in on the death rates that occur with different living situations. In the Cox-proportional hazard model, the authors used lots of variables. Some of which include travel time to facilities, number of children prior to giving birth, number of children mothers were giving birth to (twins, triplets, etc), history of abortion, delivery complications, mode of delivery, and more.

The adjusted HR gives the number of times something is more likely to occur if an infant isn’t given proper care. For instance, if infants were not exclusively breastfed, then they have a 2.5 times higher hazard of death than those babies who were exclusively breastfed. With the Cox-proportional hazard model, there were strong correlations between neonates born from mothers with complications and death, as well as travel time to hospitals and health centers with death. Infants born from mothers with no complications were 63% less likely to die than infants born from mothers with delivery complications. Women who had to travel over ten miles to healthcare facilities gave birth to babies who had a 2.5 times higher chance of dying. The Cox-proportional hazard model determines survival rates. If nothing happens to help improve the lives of these mothers and children, then the model’s survival rates will hold steady. These statistics should give enough of a reason to funnel money into Ethiopia and other countries who need it most, in order to improve upon the healthcare resources.

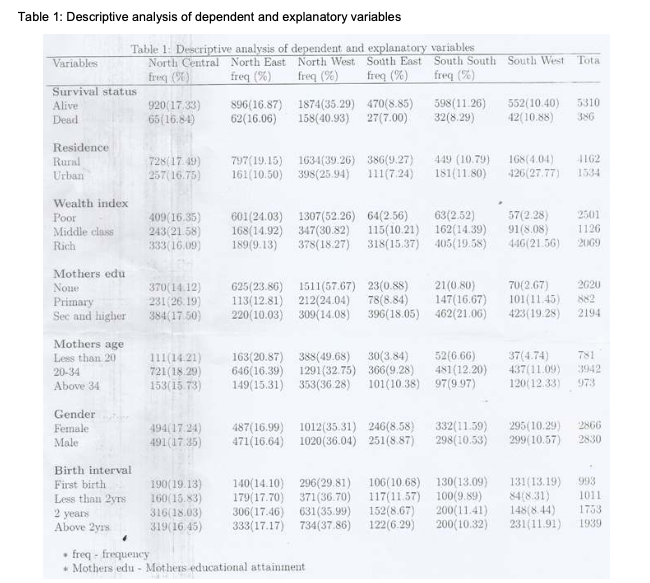

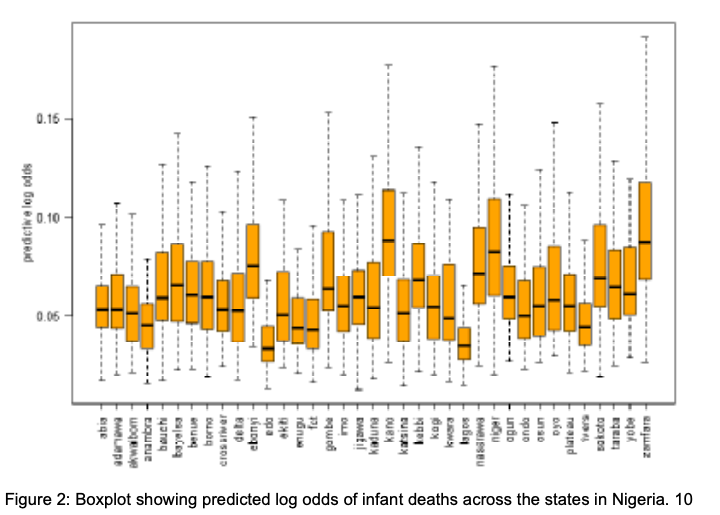

In Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling of Infant Mortality in Nigeria, the data collected was put into several different bayesian models, and was mainly used to determine the geographical aspects of the women and situations. Afterward, the authors included several boxplots charting infant death rates to show what they had discovered. The authors used data from Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. This data was processed by Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) software, Version 21. The data was then put into bayesian models for testing in this specific study. The data in this study was taken from a Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey held in Nigeria. This data includes specifics about women and children, in order to attempt to improve the women and children’s lives. This data was collected by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), and the National Agency for the Control of Aids (NACA). This study looks specifically at the 34, 376 women and the 28,085 mothers of children under five. This data just has a spatial dimension. Each variable included is either categorized as a demographic or a socioeconomic aspect. Since there is no measurement that deals with time, and only measurements dealing with what a woman’s life looks like, it does not have a temporal dimension. The validity of the data was checked using four different statistical tools: standard error, coefficient of variation, design effect and confidence intervals. Because of this, the data has been thoroughly checked for mistakes and is reliable.

In Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling of Infant Mortality in Nigeria, the authors use a Baysian model to look at the influences of infant mortality. There were two bayesian models used. The first one was a single-level bayesian logistic regression model. The individual variables were used as the predictors, and does not look at anything that could be negatively impacting the study. The second model adds in the geographics of the places the infants were born, in order to know if state and region of birth have an effect of infant mortality. The second model measures the probability that children living in the same areas are exposed to the same conditions. The authors used their individual variables and regions from which each mother resides, to determine if there was a correlation between the state where the mother lives and the condition of the infant. The authors used specifically the individual variables in the first model, in order to learn the probability of an infant dying before they reach one year. The second model included the regions in which the mothers reside. This was a bayesian hierarchical logistics model, which factors in spatial data. In the bayesian hierarchical logistics model, there are two kinds of variables used. There are the variables assigned to the demographics and socioeconomic status of the mother, such as economic status, education of mother, mother’s age, gender and previous children. There are also variables assigned to the region and area that the mothers live. The first set of variables is used for the first, and more simple bayesian model, while the second model is a hierarchical model, which includes the second set of variables as well.

These boxplots are showing the diversity in the results from the bayesian model. It is easy to see that the different places in Nigeria vary greatly in their probability of infant mortality. The difference in infant mortality between Kano, Nigeria and Lagos, Nigeria. This study found that type of residence, child’s gender, and number of children were significant determinants of infant mortality. The estimates showed that living in an urban area decreases an infant’s chance of dying greatly compared to those infants residing in a rural area. This is most likely because those in urban areas have easier and faster access to resources. The bayesian hierarchical model determines odd ratios, so much like the Cox-proportional hazard model, it’s ratio will hold if nothing is done to help the women and children of Nigeria.

These two geospatial methods in particular are becoming increasingly more helpful in predicting the outcomes of infant and maternal mortality. These models can help us to demonstrate exactly which areas, variables, and covariates need the most improvement, if this extremely high infant mortality is ever going to go down. In order to determine how to most efficiently fix the healthcare system in Ethiopia, we first need to determine exactly what needs to be fixed. By using a Cox-proportional hazard regression model, we are able to determine the survival odds of an infant living beyond the age of one. In doing so, we are able to determine the conditions in which an infant has a very low chance of survival, and ultimately funnel the most resources into these specific conditions. Travel time to healthcare facilities and an inadequacy of resources are two of the main reasons these infants are dying in Ethiopia, as can be seen by the Cox-proportional hazard regression model. With a Bayesian model, it is easily seen exactly where each infant is dying. By including geospatial data in the modeling, we are able to see which regions and cities in Ethiopia need the most improvement. There are no known Bayesian models currently being used in Ethiopia to model where healthcare facilities are housed, and where women of child-bearing age reside, so there is no way to tell which areas are in the most need of new and improved facilities.

Research Proposal

As I have spent this past semester compiling, studying and analyzing different journals and articles about the infant mortality rate in Ethiopia, I have found that there are currently no bayesian models done in Ethiopia, regarding the high infant mortality rate. I believe that using new, improved models would help contribute more evidence as to why Ethiopia’s healthcare system needs to be greatly improved. My research question, to determine if infant mortality in Ethiopia could be decreased, if women had to travel less to get to the nearest healthcare facility for post-natal care, was mostly answered by these two models. Yes. The time it takes to travel to healthcare facilities does have an effect on infant mortality, and for that matter, a great impact. By funneling in money, resources, and new healthcare facilities and hospitals, infant mortality would decrease because women wouldn’t have to travel so far to safely give birth. Ethiopian women should not have to go through the pain of losing a child simply because their country does not have the resources to take care of it’s people. Too many infants are dying in Ethiopia, and also all around the world. This could be stopped if we allocate the correct amount of resources to areas that need it. In order to truly lessen the infant mortality rate, travel time for women must be decreased.

The purpose of this research is to determine if infant mortality in Ethiopia could be decreased, if women had to travel less to get to the nearest healthcare facility for post-natal care. If this question is answered, it could mean the devastatingly high infant mortality rate could just be lessened in Ethiopia. If we were to determine if travel time had the most impact of the preposterous infant mortality rate, we could instead put forth the effort to save those babies. The current problem in Ethiopia, is that there simply isn’t enough research that can tell us exactly where it would be more efficient to allocate resources, trained healthcare professionals, and healthcare facilities. If the modelling isn’t done, there is absolutely no way to determine which areas need the most resources. Without the proper data, the Ethiopian government could potentially funnel in resources to the cities and areas that don’t need these resources quite as much as others.

All of my research has led me to suggest a certain method not yet done in Ethiopia. My research plan closely follows the scholarly article I used to analyze the Bayesian Hierarchical model. That article was based in Nigeria, however. If the same plan were followed in Ethiopia, we would be able to pinpoint the areas that have a paucity of resources, and give those areas the most attention. Not only would we capture the areas of interest, we could also determine which areas are more prone to which illnesses, diseases, and situations. These could range anywhere from areas that are more likely to not attend postnatal care, or areas where mothers are less likely to breastfeed, these sorts of conditions. This modelling could be extremely useful to discover particular areas that need work, and not terribly expensive to complete.

Considering a budget, this research could be reasonably completed. There is desktop software called Bayesialab, and it is the leading software for Bayesian networks. The pricing, for one year with this software, is $21,000. Bayesialab has great reviews, and is user-friendly, once the user knows how to work with and create Bayesian models. This part can be tricky, as Bayesian models are not always the easiest models to infer, but with a small research team filled with people with moxie, this can be done. I believe a small research team would be more useful for this research for several reasons. Firstly, it would keep costs down. The cost of a team of ten total people is much different than the costs for one hundred. Keeping it as a smaller team would mean decreased travel costs, food and accommodation costs, and for the time spent assisting with this research. A small team would also be intrinsic for maintaining an open environment. When too many people are added in, it becomes much more difficult to communicate and work. The team would need to be selected carefully, as this is a delicate matter and not for the lighthearted. We would need at least three full time researchers, that would not need to be in Ethiopia full time, but potentially would be able to go and see, rate and compare the current facilities and resources and such. Along with these researchers, we would need several other people helping the data collection and helping facilitate the day-to-day.

There are several areas in which obstacles could appear. One of which is the lack of true population data in Ethiopia. While there is census data, it is not as specific as preferred for this particular study. In the article I analyzed that dealt with this kind of modelling, the authors used data collected from a computer assisted survey. While this helped to figure out where women and infants and girls of child-bearing age lived, it was not helpful in the fact that it blocks out women without access to a computer. We need all types of women being recorded for this study to be beneficial and accurate. Because of this, we may need our researching team to go door to door, sampling women from each area of Ethiopia. This would take time and extra capital, but in the end, it would be worth it to save the lives of a potentially large number of lives. I believe utilizing this kind of data would be extraordinarily advantageous in not only improving the healthcare system for pregnant women and mothers, but also for all of those in need of better facilities. If worse comes to worse, we could simply use the data on hand, the census data, but I believe it would be better to do this research with the most specific data attainable. In gathering this research, we could help every single person in Ethiopia.

My proposal is simple: I want to use Bayesian modelling to view mother’s conditions and the region in which she lives in a new light. I believe there will be clear results as to how the current travel time to healthcare facilities is detrimental. By using Bayesian modelling we will be able to determine if an infant born in a northern region is more prone to a disease or way of death than an infant in the south. It would be pointless and absurd to have the hospitals in more urbanized areas contract the exact same number of ambulances as those in more rural areas, and this same logic applies to many things surrounding infant deaths. In order to truly combat these high mortality rates, we need to really delve into what each facility needs more of, and where new facilities need to be placed.

The proposals of my peers are strong, and research in all fields is completely valid and necessary. However, my research falls in an area that affects every person on this earth. Without proper facilities and resources, many of us may not be here today. Having a safe, clean, and close place to give birth should not be a privilege. It should be a right. Every woman on this planet deserves to feel protected when it comes to her life, and the life of her newborn child. Living in the United States, it is hard to imagine a place where infant mortality is as high as it is in Ethiopia, and it is even higher in other third world countries. In my lifetime, I have gotten to hold many newborn cousins and infants of family friends, and it is odious to think that this is not the normal everywhere. No one should have to go through the pain of losing a child or family member, and I really believe that we can help prevent treatable infant deaths in Ethiopia. There is a chance to really make a difference in the lives of mothers, and in the lives of infants who otherwise, without closer healthcare facilities may not have survived. Wouldn’t it be mellifluous to one day say that the number of infant mortalities had decreased significantly? It is this hope that has sparked my interest in researching how to best make this happen. Using Bayesian modelling could significantly raise the quality of life for so many people. A Bayesian model is the best data science method for this particular investigation because it essentially knocks two birds out with one stone. We are able to see the true main causes for death for each mother’s condition, and also determine which causes of death are more prevalent in each region. Utilizing this data correctly would be very efficient and would help start the ball rolling on making Ethiopia a place in which mothers don’t have to be fearful of their infants dying because of preventable and treatable conditions. A decrease in travel time and an increase in adequate resources and properly trained healthcare professionals, would likely yield a higher standard of living for many Ethiopian women, as well as decrease the shockingly high infant mortality rate for Ethiopia, and I believe this research could help this become a reality.